Most analysts expected the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act to boost economic output modestly in both the short and the longer run. The evidence supports the prediction for the short run. Because they are confounded by the large and lasting effects of the COVID pandemic and related policies, we will probably never be able to disentangle the long-term effects. However there was little evidence of a strong effect on investment that could lead to higher longer-run growth in the years before the pandemic.

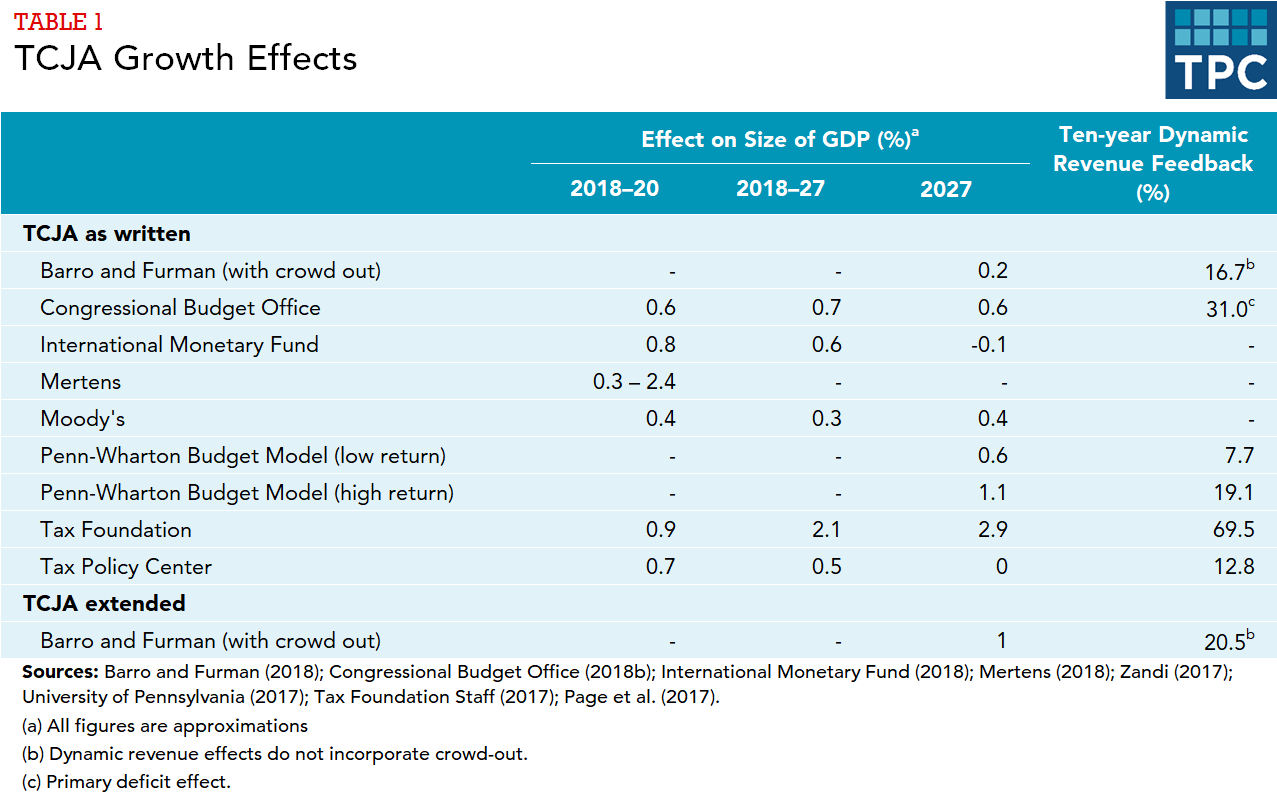

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) reduced tax rates on both business and individual income, and enhanced incentives for investment by firms. Those features most likely have raised output in the short run and will continue to do so in the long run, but most analysts estimate the modest effects offset only a portion of revenue loss from the bill (table 1).

The TCJA likely influenced the economy primarily by raising demand for goods and services in the first couple of years. Cuts to individual income taxes meant that most households had more after-tax income, which likely increased their spending. In addition, provisions such as allowing the expensing of some capital investment may have increased investment spending by firms. As businesses see more of their goods being purchased, they respond by ramping up production, boosting economic output. The annual growth rate of GDP rose from 2.4 percent in 2017 to 2.9 percent in 2018 , , likely due largely to the effects of TCJA on demand. However, the growth rate slowed back down to 2.3 percent in 2019.

Those short-run effects were likely modest for two main reasons. First, much of the tax cuts flowed mostly to higher-income households or to corporations, whose stock tends to be held by the wealthy. Higher-income households spend less of their increases in after-tax income than lower-income households. Second, the tax cut was enacted at a time when unemployment was low and output was near its potential level. Therefore, the increase in demand was offset by tighter monetary policy, as the Federal Reserve held interest rates higher than they otherwise would have been to prevent an increase in inflation.

In the longer run, the TCJA likely will affect the economy primarily through increased incentives to work, save, and invest. Reductions in individual income tax rates mean that workers can keep more out of each additional dollar of wages and salary. That encourages people to work more hours and draws some new entrants into the labor force. However, those reduced rates are scheduled to expire at the end of 2025; after that, there is little or no tax incentive to increase work.

Lower individual tax rates, a lower corporate tax rate, expensing of capital investment, and other reductions in business tax rates increase the after-tax return to saving, encouraging households to save and reducing the cost of investment for firms. Those changes likely will result in more investment, a larger capital stock, and higher output. However, it is not possible to isolate the effects of TCJA due to the confounding influence of more recent developments, such as the COVID pandemic and related legislation, as well as other policies, such as trade restrictions and green energy subsidies.

Any increase in investment must be financed by a combination of private saving, public saving (or government budget surpluses), and net lending from abroad (which could take the form of bond purchases, portfolio investment, or direct investment of physical capital). Most analysts, consistent with empirical research, estimate that private saving rises only modestly in response to an increase in the after-tax rate of return. And the bill has reduced public saving, by increasing the deficit. Therefore, much of any increase in investment from TCJA is likely financed by net foreign lending. That increases the portion of domestic output that flows to foreigners in the form of interest and profit payments, reducing the fraction of the higher output available to Americans. For that reason, in examining the effects of TCJA it may be more illuminating to look at changes in gross national product (which subtracts that type of payment) rather than gross domestic product (which does not). For example, the Congressional Budget Office projected that TCJA would boost GDP by 0.6 percent in 2027, but that—taking account of increased payments to foreigners—GNP would be up by only 0.2 percent.

We can probably never make a good estimate of TCJA’s long-run impact on investment, due to the effects of the pandemic. But there was little evidence of a strong effect in the pre-pandemic years. Investment rose in 2018, but research by the IMF suggests that the increase stemmed mostly from the short-run boost to demand. Supporting that notion, a Congressional Research Service analysis found that the types of investment that rose in 2018 were not those whose costs were reduced most by TCJA (as one would expect if the increases were driven by long-run cost factors rather than short-run demand).

Updated January 2024

Barro, Robert J., and Jason Furman. 2018. “Macroeconomic Effects of the 2017 Tax Reform.” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Congressional Budget Office. 2018. “The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2018–2028.” Appendix B. Washington, DC: Congressional Budget Office.

Gale, William G., and Claire Haldeman. 2021. “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act: A test of supply-side economics.” Washington DC: Brookings Institution.

Gravelle, Jane G., and Donald J. Marples. 2019. “The Economic Effects of the 2017 Tax Revision: Preliminary Observations.” Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

International Monetary Fund. 2018. “Brighter Prospects, Optimistic Markets, Challenges Ahead.” World Economic Outlook Update. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Joint Committee on Taxation. 2017b. “Macroeconomic Analysis of the Conference Agreement for H.R. 1, The “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” JCX-69-17. Washington, DC: Congress of the United States.

Kopp, Emanuel, Danial Leigh, Susanna Mursula, and Suchanan Tambunlertchai. 2019. “U.S. Investment Since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017.” IMF Working Paper No. 19/120. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Mertens, Karel. 2018. “The Near-Term Growth Impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Research Department Working Paper 1803. Dallas: Federal Reserve Bank.

Page, Benjamin R., Joseph Rosenberg, James R. Nunns, Jeffrey Rohaly, and Daniel Berger. 2017. “Macroeconomic Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Washington DC: Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center.

Tax Foundation Staff. 2017. “Preliminary Details and Analysis of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.” Special Report No. 241. Washington, DC: Tax Foundation.

University of Pennsylvania. 2017. “The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, as Reported by the Conference Committee (12/15/17): Static and Dynamic Effects on the Budget and the Economy.” Penn Wharton Budget Model. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania.

Zandi, Mark. 2017. “US Macro Outlook: A Plan That Doesn’t Get It Done.” Moody’s Analytics (blog), December 18.